Darkroom Week

Introduction

Ask anyone who still shoots film in 2015 why they do it and most will have the same answer: Because I like the look and feel of film. Or because they like the challenge of getting that one frame to come out perfectly, when you can waste a thousand digital shots and not lose any money in your pursuits. Or because of sheer gleeful nostalgia; hey, all reasons are valid - we don't judge.

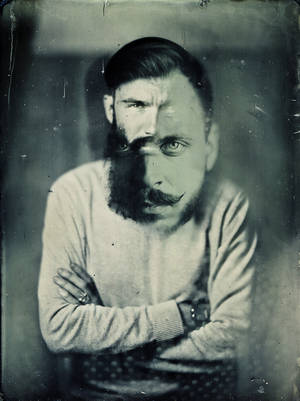

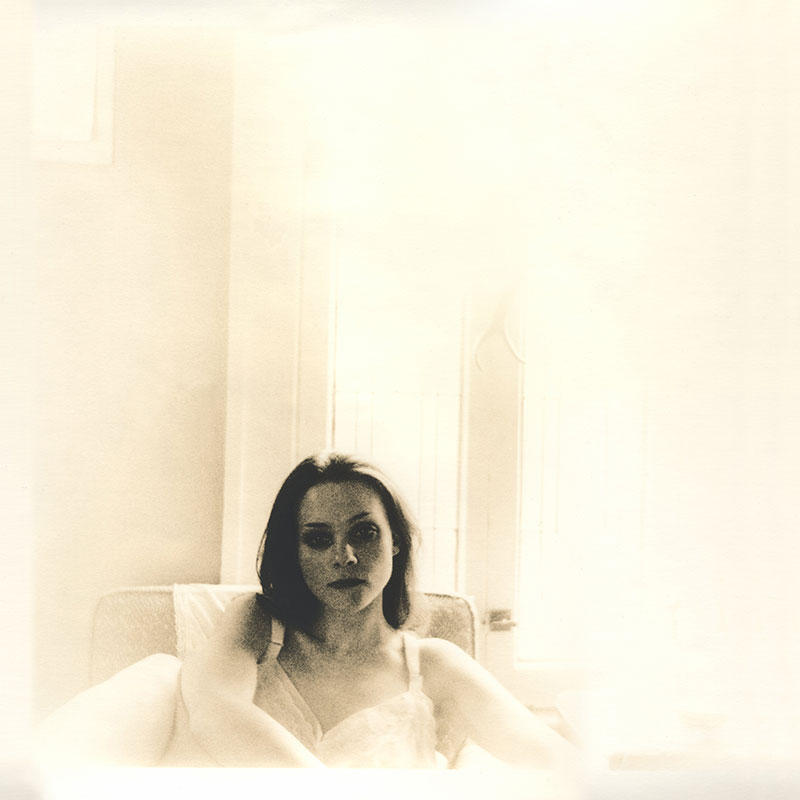

Surprisingly not the average contemporary film photographer

It's for a lot of the same reasons that some people like using alternative photographic processes too - each process gives the print or negative a very unique tonal range, coloration, and other feels-y elements that can work toward a vintage look or something more experimental and playful. In this article we're going to look at some of the common alternative processes, discuss why they still have adherents in the Instagram world, and look at some wonderful examples of thinking outside the silver-gelatin box.

Surprisingly not the average contemporary film photographer

It's for a lot of the same reasons that some people like using alternative photographic processes too - each process gives the print or negative a very unique tonal range, coloration, and other feels-y elements that can work toward a vintage look or something more experimental and playful. In this article we're going to look at some of the common alternative processes, discuss why they still have adherents in the Instagram world, and look at some wonderful examples of thinking outside the silver-gelatin box.

The Really Primitive

- Crush some mint in a mortar and pestle

- Apply the mint juice to a piece of heavy paper

- Put a transparency of a negative on top of the paper and put in the sun for a day or five

- ???

Yes, some alt processes are really that easy - and those steps will get you a print, albeit one that's pretty uniformly light green, not very lightfast, and low contrast. But try it with some red poppy or violet flowers and you'll have a pretty damn stellar anthotype, probably the simplest of the photographic processes. In the anthotype process you're exploiting the ability of visible and UV light to degrade plant pigments - so the results aren't going to hold up to a lot of sun exposure, since there's no "fixing" step to desensitize the plant emulsion to future light. What do the end results look like? Kind of like a salad.

I crack myself up.

I crack myself up.

Actually, depending on the plant material used and the contrast of the negative being printed or the object being photogrammed, they tend to look like a traditional print-making print of some sort. This is a sample of a double-exposed anthotype photogram:

And this one's an anthotype negative made on beetroot from a photographic transparency, inverted and desaturated in digital post-process:

Now, a couple paragraphs up I used the term "photogram", and if you've not heard of that before - that's another fairly primitive method of making a print but it's also one that can be used with almost any process. A photogram is just printing a light-sensitive medium in direct contact with an object. Even contact sheets in a normal silver-gelatin process are photograms, sort of. Photograms can be used to great effect to make more abstracted photo-based works, like in the following using a silver process:

Some people also use inks, dyes, anthotype mixtures, and other processes as substrates for photograms - and some require post-exposure development (like silver processes need developed and fixed) while some are good to go as soon as they're exposed. One specific photogram technique worth mentioning is the Lumen Print Process, which has always baffled me so I'll explain it as "you make a photogram on undeveloped photographic silver paper in sunlight, rinse it in water, and then fix it without developing and a magic image appears like magic". Lumen prints tend to have softer edges and contrasts than most other photograms, giving them a dreamy and almost three-dimensional quality as demonstrated in this sample of a few pieces of moss and fern:

Now, a third process that I'm calling "primitive" isn't primitive, but it's the last one I'll be discussing that doesn't require you to buy enough industrial-grade chemicals to concern the authorities. If you already develop gelatin-silver prints, you can print on a wide variety of surfaces using your regular paper chemistry by using Liquid Emulsion. In essence liquid emulsion turns any surface into a piece of standard black-and-white photographic paper, be it a sheet of watercolour paper:

Or a ceramic tile:

Or a leaf:

And obviously the benefit here is that you're giving texture, tone and (in the case of weird substrates like that leaf) some really unique canvas shape to your print. I've seen trompe-l'oeil anamorphosis stuff printed inside of bowls before, probably by someone with more free time than he should have had, but still. Liquid emulsion also allows for much bigger printing than standard sizes of photo paper; the guy I bought my enlarger off did a liquid emulsion mural in a house once. Again, since this is a silver process you just develop the emulsion like you would normal photographic paper - or with a brush covered in developer, water, and fixer if it's on something too big or upright to immerse in your chemistry.

Daguerreotypes are hard, okay? You have to make a buffed silver plate and then sensitize it with iodine, bromine or chlorine fumes and then develop it with mercury fumes and that's a whole lot of chemicals that we didn't even play with in university inorganic chemistry without fume hoods and face shields. I'm assuming that's why, in spite of daguerreotypes being the "iconic" vintage process - and the first major photographic process - there are no examples of daguerreotypes showing up in DA search.

Also because the users who made daguerreotypes ended up looking and behaving like this, what with the mercury

The "Typical" Vintage Processes

Daguerreotypes are hard, okay? You have to make a buffed silver plate and then sensitize it with iodine, bromine or chlorine fumes and then develop it with mercury fumes and that's a whole lot of chemicals that we didn't even play with in university inorganic chemistry without fume hoods and face shields. I'm assuming that's why, in spite of daguerreotypes being the "iconic" vintage process - and the first major photographic process - there are no examples of daguerreotypes showing up in DA search.

Also because the users who made daguerreotypes ended up looking and behaving like this, what with the mercury

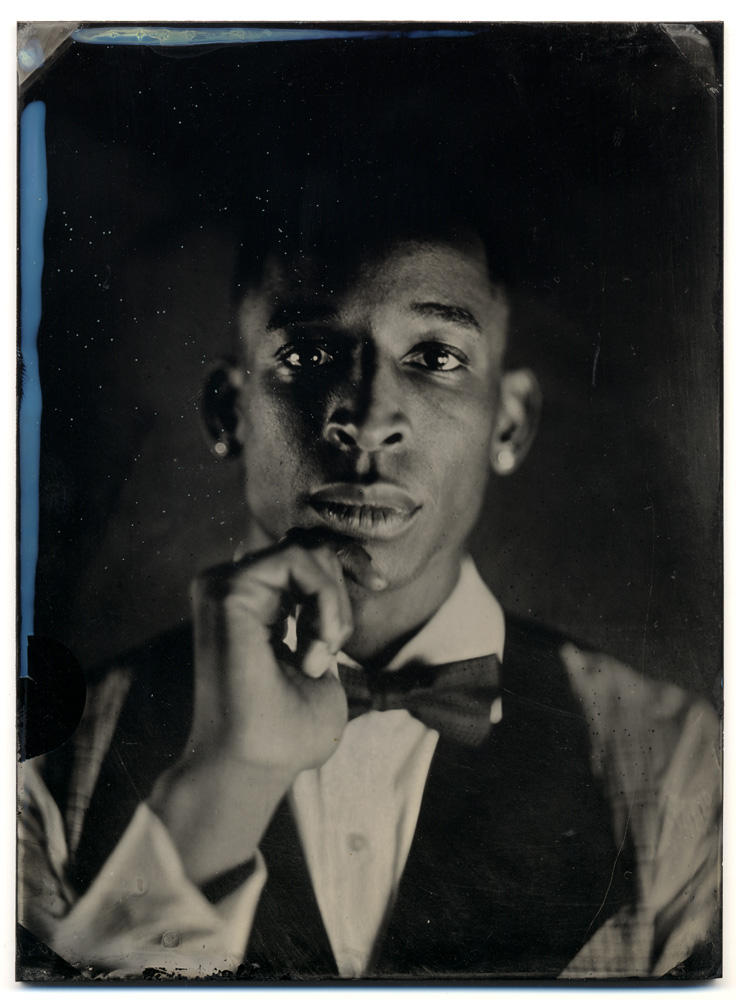

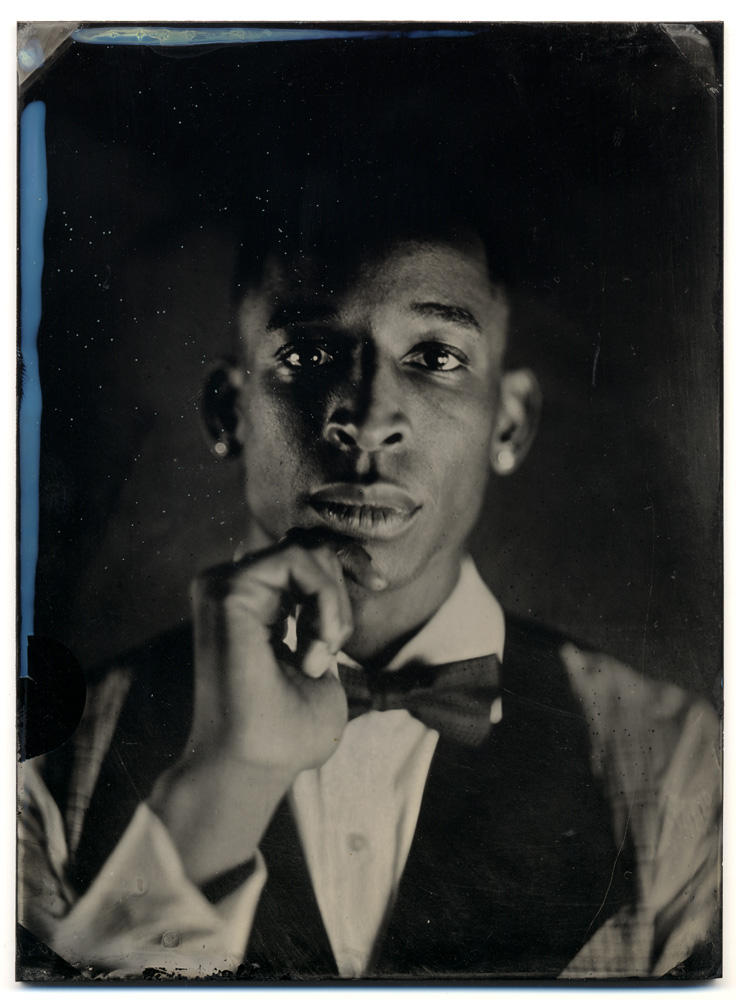

Being disappointed with the fact that daguerreotypes only made non-duplicable positive images, and calotypes - an early negative process using silver iodide on paper - made paper negatives that weren't very durable, Frederick Scott Archer invented the Collodion Process, the first historic photographic process to still have a wide penetration on DA and a big modern following for their inherently archaic look and delicious tonal ranges. You may recognize the typically rough edges, the shallow depth of field (more an effect of the large format than the process used), and the typical scratches where the emulsion gets nicked during the process.

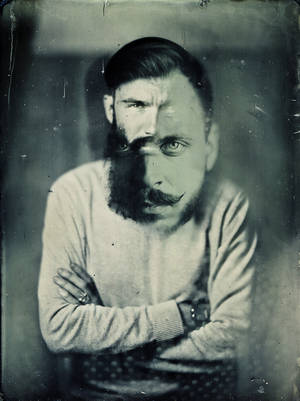

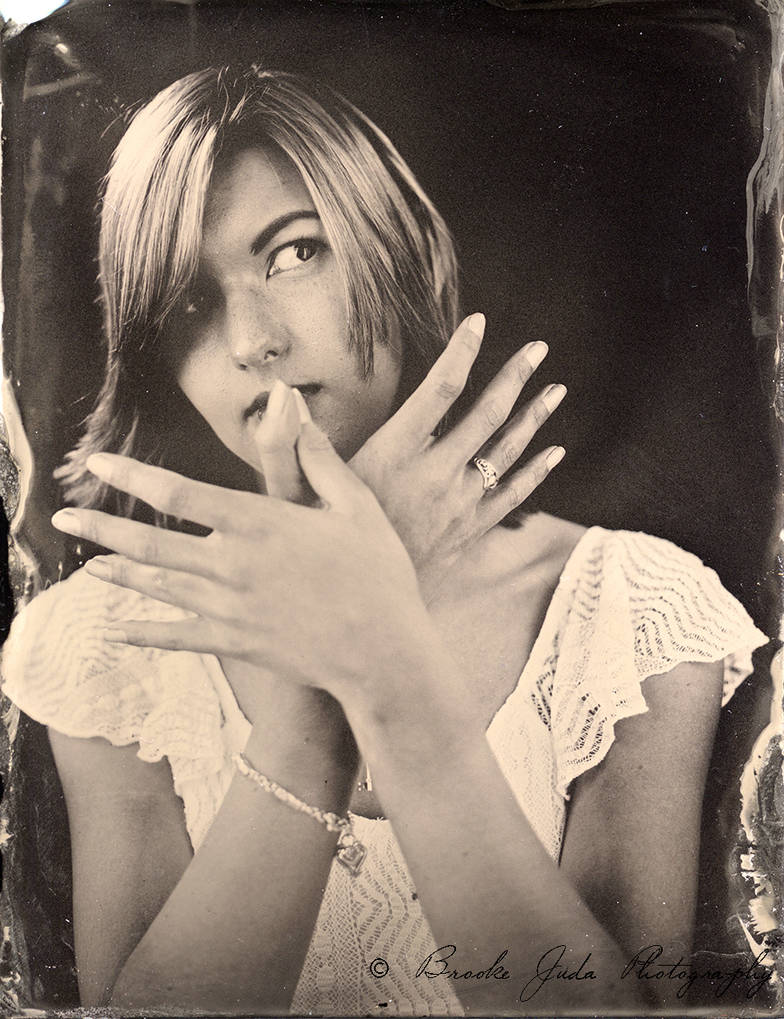

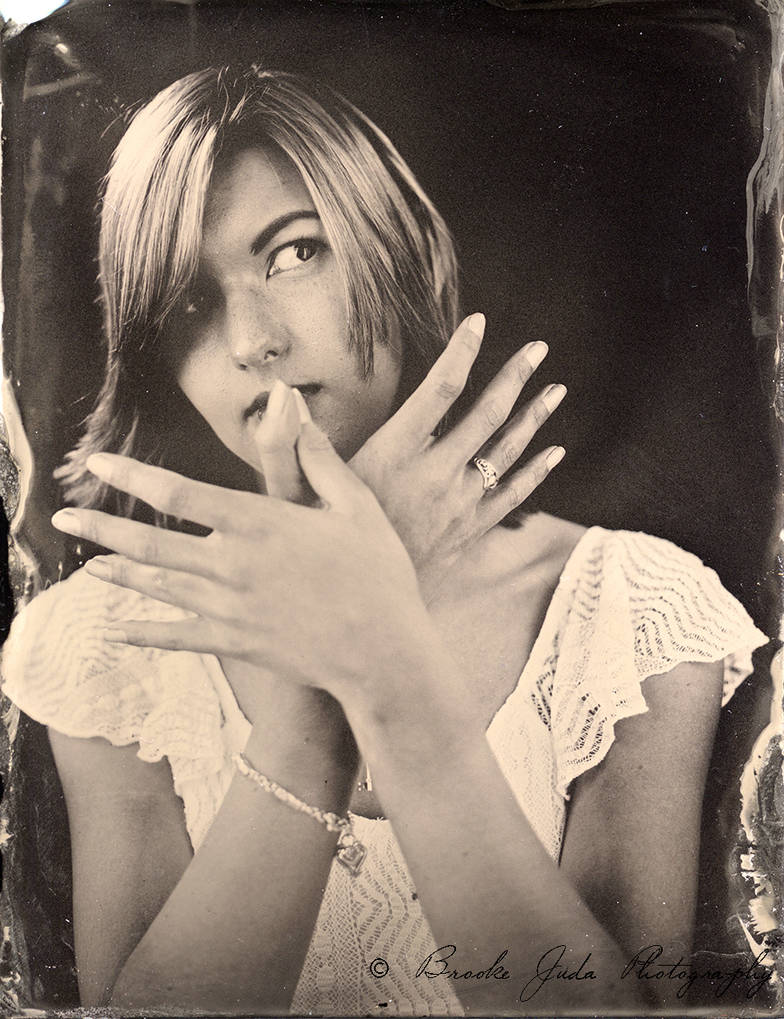

Wetplate collodion, the collodion process you see the most of on DA, uses a silver bromide solution on a glass plate to make a transparent negative. Positives were made use the collodion process in two major ways, apart from printing on albumen paper - the Ambrotype and the Tintype. Both processes rely on printing the lighter colours as opaque and the darker as transparent, with the tintype being printed onto sheet metal that would usually be lacquered black, and the ambrotype printed onto a plate of glass typically backed with black velvet. A contact print from a wetplate collodion negative onto a prepared tin- or ambrotype creates a 1:1 positive reproduction. The difference between the two processes on the aesthetic quality of the finished product is negligible, here's a tintype:

And here's an ambrotype:

Both have rich contrasts and maintain the general qualities of the original negative. Tintypes, being not glass, are less likely to break if you drop them on the floor though.

The Other Processes

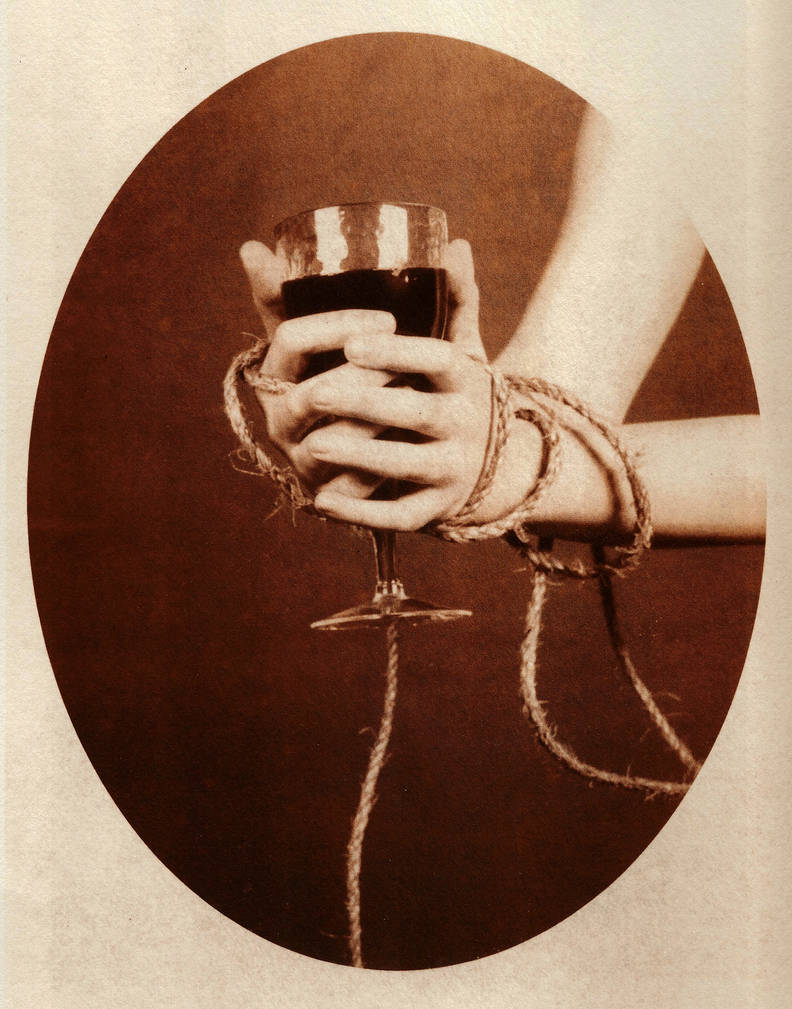

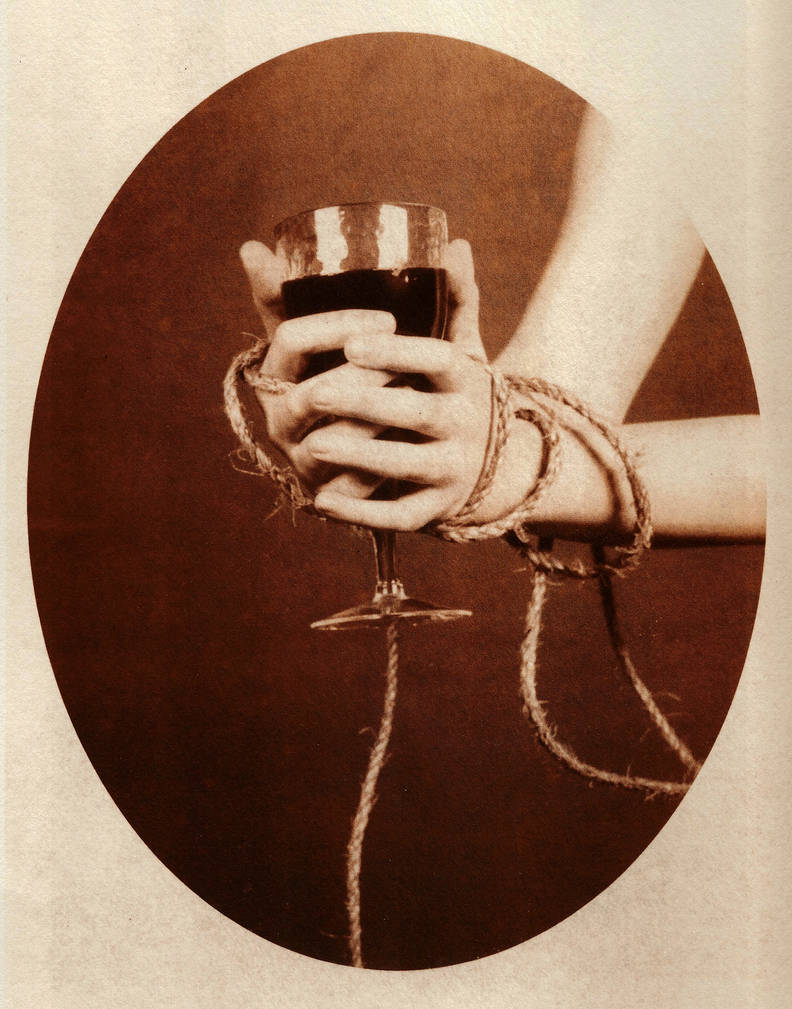

Want to get a consistent, continuous tone like a silver print but a bit more control over contrast and unrivaled archival permanence? The Platinum/Palladium Process is the choice for you. Using iron with chlorine, platinum and/or palladium like liquid emulsion you can print very "normal"-looking prints on your choice of surface texture, like this one that looks to be on watercolour paper:

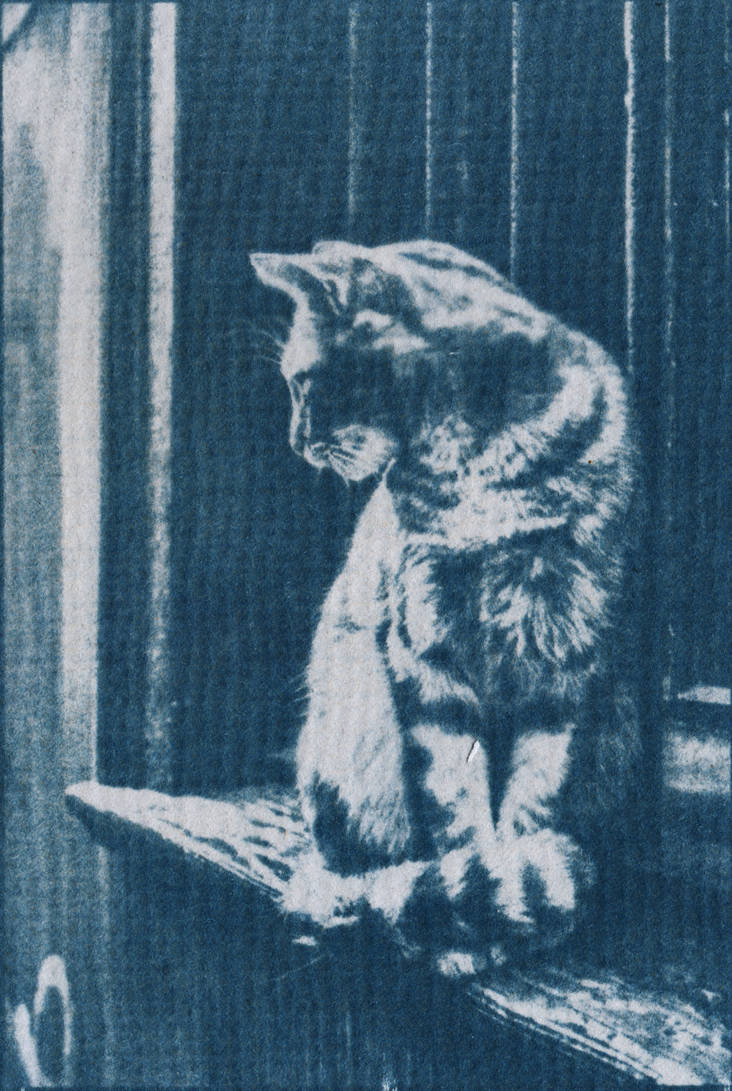

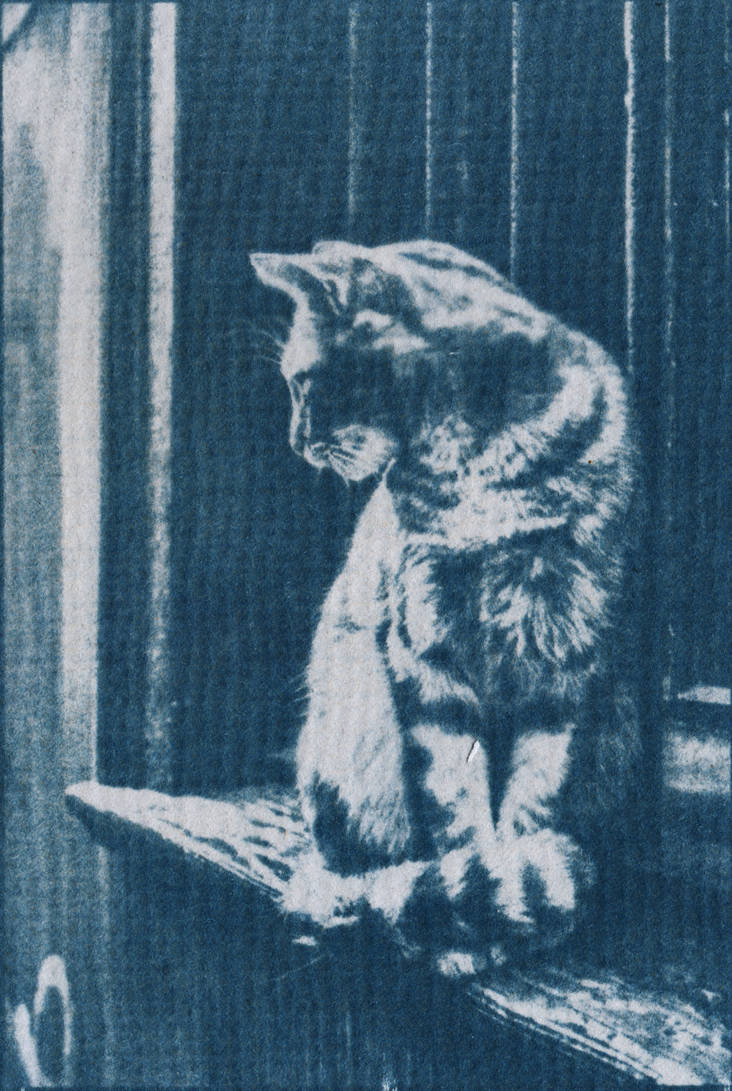

Or maybe you want that same texturing and contrast but with the true blue monochrome of Cyanotype:

Both processes can be contact-printed from large format negatives or computer-printed negative transparencies, in natural sunlight - and are light-fast, unlike anthotypes and ink-based photograms. Or stick with silver, and make a contact-printed, instantly-developing but gritty-looking Salt Print, which is also archival once fixed:

If you're using standard silver paper, you can still get an alternative outcome by using lith developer on an overexposed paper to make a higher-contrast, grainier-than-normal Lith Print. Fun thing with lith dev? The longer you use the same batch of developer, the more unreliable the colour tone you get becomes. But the initial warm monochrome is beautiful, too:

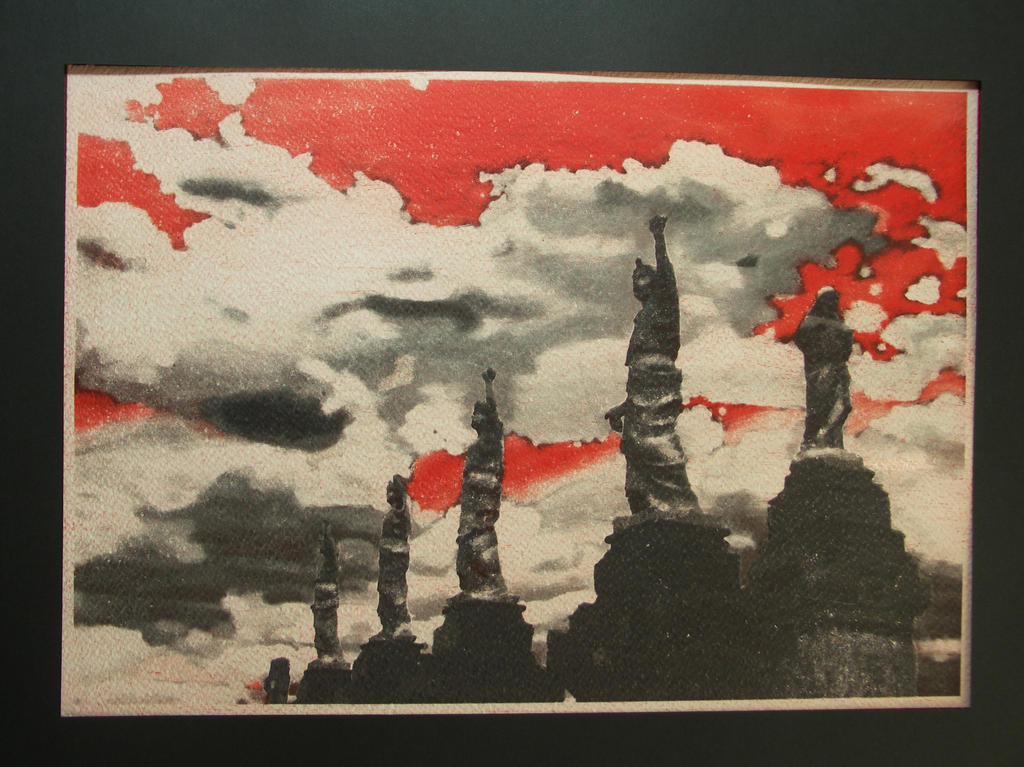

And, in case all those processes looked too normal for you, there's always the Gum Bichromate Process - which uses pigments and gum arabic to create monochrome, duotone or even full-colour images. Some people use the bichromate process to make very rich, high-saturation colour prints:

Or monochromes that always remind me of Jack the Ripper for some reason:

Or some stuff that I just look at and think "ART!" like a toddler might, because sometimes I am bad at expressing my feels:

And In Conclusion

Much like people use film to evoke specific moods, dynamics or "feels" in their shots - and that keeps a special place for film in the modern photographic arts - so too do people use alternative processes. Choosing a process can be as important as choosing a subject, since both lend heavily to the finished image and the emotions and thoughts it will provoke in the viewer.

Gif is unrelated.

Alt processes aren't necessarily cheap and easy but they are still useful tools to have at your disposal as a photographer. Even if you never use them. You never know, after all, when you might take that one nearly-perfect shot and think "Hmm, wouldn't that look good printed in catnip?"

Gif is unrelated.

Alt processes aren't necessarily cheap and easy but they are still useful tools to have at your disposal as a photographer. Even if you never use them. You never know, after all, when you might take that one nearly-perfect shot and think "Hmm, wouldn't that look good printed in catnip?"